Water: the driver of changing rural landscape patterns

Jane L. Lennon AM, PhD, M.ICOMOS

[presented at 2019 ICOMOS/IFLA ISCCL Meeting Dublin, Ireland]

Abstract:

Australia is experiencing one of its cycles of drought across the east coast and floods in the far north. This leads to calls for more harnessing of rivers for industrial supply -an agribusiness culture supplanting one which knew how to exist with the environmental cycles.

After World War 2 the largest and major river system in Australia was engineered into a system to deliver irrigation and town water downstream from the Snowy Mountains to South Australia. This led to increasing rural farm productivity but at a cost of obliterating former patterns of Aboriginal and pastoral use around the water courses.

A new Commonwealth Water Act in 2007 enabled water to become a tradeable commodity and this, coupled with a series of droughts has led to ageing farmers selling their water rights for more than their land value and retiring to urban centres. Patches of dead orchards and vineyards testify to this. But the richer agribusinesses, especially those growing cotton, have expanded as they purchase more water allocations. The result is a demographic movement of farmers, small town suppliers, service providers and the stranding of poorer communities with no seasonal jobs. Abandonment on the edges of settlements, laser levelled enormous paddocks stretching into the distance, loss of paddock trees and old access tracks mark these landscapes.

Conservation of the rural landscape in private ownership is achieved by planning scheme controls but except for building code requirements, much of farming activity is a permitted use in the rural zone and so the landscape is transformed by the death of a thousand cuts.

Our World Rural Landscape Principles B.3 of implementing strategies of conservation, repair, innovation, adaptive transformation, maintenance, and longterm management. need to address these sorts of rapidly changing landscapes.

Introduction

I wish to acknowledge my ancestors who came to Australia from the well- watered Emerald Isle -the O’Sullivans, Hayes and O’Dywers from Limerick and the O’Connors from Cork in the late 1830s and 1850s.

A history of Australia, the driest inhabited continent, could be centred around water resources. Crossing the seas to land on coastal shores then searching for trickling streams or navigable rivers and settling nearby. Moving across the continent following watercourses, billabongs and meanders, chains of ponds, marshes and swamps, wells in rocky terrain and trees that marked soaks underneath. Aboriginal people had learnt how to collect water over 65,000 years of great climatic variation. The first settlers 230 years ago followed their pathways and slowly learnt where to find water away from the obvious rivers.

The so called ‘well-watered lands’ of south-eastern and southwestern Australia and the eastern coastal belt were occupied first by European settlers who were land hungry and selected the alluvial valleys. Pastoralists took up large tracts of land for their grazing stock (Pearson and Lennon, 2010). The search for grass for ever expanding empires for these kings in grass castles led to cross continent movements and to the tidal estuaries of the vast northern tropical rivers. These rivers were regarded as highways to Asia for exports of livestock. But in the areas of reliable rainfall, farmers carved out a landscape of 640 acre blocks imprinting them with European style crops and livestock watered from nearby creeks. Later, in the early twentieth century farm landscapes were created from windmill pumped Artesian Basin water and irrigation systems.

Fig. 1: Artesian water for the Inland

After World War Two, as part of the vision for building the nation, the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme was developed. This involved engineering the headwaters of the Murray, Eucumbene, Snowy Rivers to create power stations and to increase the volume of water flowing down the Murray for irrigation. It was completed in 1974 and is one of the largest engineering schemes ever built in Australia, and is nationally important for its engineering achievements. Between 1949 and 1974 the scheme employed over 100,000 people, from over thirty different nationalities, and is significant in the history of Australia’s post-World War Two migration.

Fig. 2: Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme (1949-1972)

Water for multiple use?

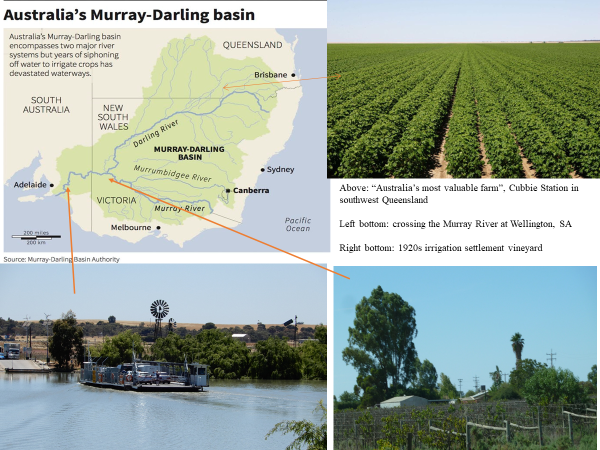

The Murray-Darling Basin is a very productive agricultural zone and its rivers have been used to boost agricultural outputs through irrigation. State governments spent much of the 20th century allocating this water to agricultural users. By the 1990s it was clear too much water was being extracted. This resulted in both harm to the river environment and potential reduced reliability for those with existing water rights.

These water harvesting schemes were developed before environmental and heritage legislation was introduced in the 1970s. Increased areas of land were made productive by irrigation and this meant that many patterns of Aboriginal occupation and later pastoral use around water courses were obliterated by the new works. Previous cultural landscapes were subsumed into another with unrecognisable attributes -no palimpsest of layers survived.

The Commonwealth Water Act 2007 enabled water to become a tradeable commodity and this, coupled with a series of droughts has led to farmers selling their water rights for more than their land value and retiring to urban centres. Others cannot afford the funds for bidding at auction for water allocations so they sell up their farms. Patches of dead orchards and vineyards testify to this. The richer agribusinesses, especially those growing cotton, have expanded as they purchase more water allocations.

Fig. 3 Murray Darling Basin

The result is a demographic movement off the land - of farmers, small town suppliers and service providers. Poorer communities are left stranded with no permanent or seasonal jobs. Abandonment on the edges of settlements, laser levelled enormous paddocks stretching into the distance, loss of paddock trees and old access tracks mark these landscapes.

Conservation of the rural landscape in private ownership is achieved by local government planning scheme controls, State-wide vegetation retention controls or individual farmer decisions. However, except for building code requirements, much farming activity is a permitted use in the rural zone and so the landscape is transformed by the death of a thousand cuts, and sometimes by rapid sweeps of the bulldozer.

ICOMOS World Rural Landscape Principles

ICOMOS adopted the World Rural Landscape Principles in 2017 for use in professional heritage conservation. It would seem that principle B. 3 - Define strategies and actions of dynamic conservation, repair, innovation, adaptive transformation, maintenance, and longterm management, would be met by the Murray Darling Basin Plan (ICOMOS GA2017).

The Murray-Darling Basin Plan which was passed in 2007 in the national parliament with bipartisan support aims to return water and restore the health of the rivers. The Plan is one of the main components of the Commonwealth Water Act, committing to return 2750 gigalitres of environmental water to the two rivers. The Plan achieved over half of the target by 2013, mostly through buying water from farmers. But then a new government shifted focus away from farmers to installing water-saving infrastructure, for which taxpayers paid for an expensive but inefficient strategy (Crase, 2013).

Water is big business, big politics and a big player in our environment. It is liquid gold. Taxpayers have spent A$13 billion on water reform in the Murray-Darling Basin in the past decade. At its foundation, Australian water reform is based on four pillars.

1. Environmental water and fair consumption to help restore the Basin’s health and also to ensure that water users along the river would have fair access to water.

2. Water markets and buybacks to allow water to be purchased on behalf of the environment, and to allow water permits to be traded between irrigators depending on relative need.

3. States retain control of water because of states’ water-management responsibilities but the Commonwealth’s obligations to the environment mean that the Murray-Darling Basin Authority cannot easily enforce action on the ground.

4. Trust and transparency is the foundation for water trading and has helped to make water use more flexible. In a dry year, farmers with annual crops (such as cotton) can choose not to plant and instead to sell their water to farmers such as horticulturists who must irrigate to keep their trees alive. This flexibility is valuable in Australia’s highly variable climate (Thompson, 2017).

The environmental benefits are slowly but surely being seen at specific sites, although these have not been replicated Basin-wide, and ecologists believe that it will take decades to restore the rivers to health (Webb, 2018). Ecological evidence shows the Barwon-Darling River is not meant to dry out to disconnected pools – even during drought conditions.

Fig. 4 Darling River, Nov 2017

Water diversions have disrupted the natural balance of wetlands that support massive ecosystems. Meanwhile traditional owners along the Darling River, the Barkindji, have lost their water, fishing and riparian associations (Norman and Janson-Moore, 2019), and small holders on the edges of towns have lost their orchards. Rural landscape strategies are not working for these communities.

Fig. 5 An Aboriginal flag planted on the riverbed

Adaptation?

Australia is renowned as a land of droughts and flooding rain -for the past 500 years as shown by tree and coral studies. But across Australia in 2018 temperatures increased, rainfall declined further, and the destruction of vegetation and ecosystems by drought, fire and land clearing continued. Soil moisture, rivers and wetlands all declined, and vegetation growth was poor.

The 2018-19 summer broke heat records across the country by large margins. More than a million hectares of bush and farmland were destroyed by bushfires – the largest expanse of Queensland affected since records began, bushfires raged through Tasmania’s World Heritage forests, and a sudden turn in the hot weather killed scores of fish in the Darling River, which had run dry. The monsoon in northern Australia did not come until late January, the latest in decades, but then dumped dumping 681 millimetres of rain in just 24 hours on northern Queensland, then flooding rains covered more than 13.25 million hectares of northern Queensland, killing hundreds of thousands of drought-stressed cattle. Many people are still climate change sceptics cocooned in cities from the harsh realities of rural life and many suggestions for drought-proofing Australia by harnessing the tropical floodwaters have been made in ignorance of the environmental impacts and costs (Austin, 2019).

In Australia we all live downstream and while changing farm and land-use practices around rivers can improve water quality ‘cheaply’, these practices may have only a modest effect on biodiversity overall – especially if the land next to rivers is degraded. There have been improvements in a few catchments throughout Australia such as in Queensland. Yet many other catchments nationally continue to deteriorate in water quality and biodiversity. Landholders need incentives to protect streamside vegetation, including payments to replant vegetation, alongside better farm and land management. We all stand to benefit from protecting biodiversity and repairing our waterways (Mantyka-Pringle et al., 2018). Despite so many plans for more dams, there is still so little water as there has been little rain, and what water there is costs too much - at $500 to $600 per megalitre it is not worth growing rice and the cotton crop has decreased 54% this year (Higgins, 2019).

Fig. 6 Declining productivity in the prime agricultural zones [Source: ABARES 2017]

Challenges

Television and media reports have made the extreme weather events come to the attention of most Australians and climate change was a major issue in the 2019 national elections. But currently Australia has no national strategy to tackle climate change (Glasser, 2019). City folk turn on their taps but need to realise that their water is a diminishing gift from the cultural landscape of rivers and reservoirs.

The challenge is to put our World Rural Landscape principles to work through awareness raising, equitable sharing of resources and engaged action to maintain the culture and nature of our water sources, the purveyors of life. We are morally responsible for the health of our landscapes. Despite current manifestations of climate change revolving around water with too much or too little, inexplicably business as usual persists among the political classes, chief executives and the media, expressing a plethora of half-truths and lies, defying the original definition of the species as ‘sapiens.’

References

ABARES 2017. [Hughes, N, Lawson, K & Valle, H 2017, Farm performance and climate: Climate-adjusted productivity for broadacre cropping farms, Canberra, research report no.4, p. 3.]

Austin, Peter. 2019. ‘It’s time to harness our rich endowments’, The Land, NSW, 31 Jan 2019

Crase, Lin, 2013. Changes to Murray-Darling plan try to make water run uphill, The Conversation, 11 October 2013

Crase, Lin, 2019. Australia’s ‘watergate’: here’s what taxpayers need to know about water buybacks, The Conversation, April 23, 2019

Glasser, Robert, 2019. Australia needs a national plan to face the growing threat of climate disasters, The Conversation March 8, 2019. See also The Strategist, 6 March 2019.

Higgins, Ean, 2019. ‘So many plans for so many dams but still so little water’, The Australian, Inquirer, 15-16 June 2019: 18

ICOMOS GA 2017 6-3-1 – Doctrinal Texts, ICOMOS-IFLA Principles Concerning Rural Landscapes as Heritage.

Mantyka-Pringle, C., Rhodes, J and Martin T., 2018. We all live downstream – it’s time to restore our freshwater, The Conversation, 9 May 2018

Norman Heidi and John Janson-Moore, 2019. Death on the Darling, colonialism’s final encounter with the Barkandji, The Conversation, April 5, 2019

Pearson, Michael and Jane Lennon, 2010. Pastoral Australia, Fortunes, Failures and Hard Yakka, a historical overview 1788-1967, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood.

Thompson, Ross, 2017. Is the Murray Darling Plan broken? The Conversation, July 26, 2017

Webb, Angus [ed]. 2018. It will take decades, but the Murray Darling Basin Plan is delivering environmental improvements, The Conversation, May 1, 2018

![Fig. 6 Declining productivity in the prime agricultural zones [Source: ABARES 2017]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58adf66a414fb5327e1bff20/1581385814794-NR6MBUPFPGYXMKBAW3H6/Fig.+6+Declining+productivity+in+the+prime+agricultural+zones+%5BSource%3A+ABARES+2017%5D)